Background and Rationale

Photo Credit: APC Benin

At the 2013 International Family Planning Conference in Addis Ababa, Benin formally announced a commitment to increase the contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) to 20 percent by 2018, a goal that was affirmed with the launch of the National Costed Family Planning Plan for 2014–2018. According to the 2012 Demographic and Health Survey (EDSB6- IV), the national CPR for modern methods was 7.9 percent, with family planning use higher in urban areas (9.5 percent) compared to rural (6.8 percent). Between 2006 and 2012, the use of modern contraceptive methods increased marginally (from 6.1 to 7.9 percent), whereas the unmet need for family planning increased from 27.3 percent to 32.6 percent (EDSB-IV, 2012).

Global evidence on community-based access to injectable contraceptives (CBA2I) shows that trained community health workers can safely and effectively provide injectable contraceptive services. In addition, international guidance promotes the introduction, continuation, and scale-up of this service delivery model.1 The introduction of injectable contraceptives at the community level is considered a key component to achieving Benin’s 2018 CPR target because it will expand access to family planning services for women.

Until recently, women in Benin could receive injectable contraceptives only in a health center, thus limiting access in rural communities. In 2014, the Benin Ministry of Health (MOH) Mother and Child Health Directorate (Direction de la Santé de la Mère et de l’Enfant/DSME) approved a pilot project to allow health workers known as aides-soignantes to provide injectable contraceptives (i.e., Noristerat) in the community and in health centers. Aidessoignantes are a para-professional cadre of nurses’ aides who assist qualified personnel at health centers by providing services such as immunizations. They generally originate from the community in which the health center they support operates. The pilot, known as the Advanced Strategy, was implemented by the DSME through the Advancing Partners & Communities (APC) Project, with the support of USAID/Benin and USAID/Washington.

The MOH selected the district of Adja-Ouere in the Plateau region in southern Benin as the site for implementation of the Advanced Strategy. This district is part of the Pobe-Adja Ouere-Ketou health zone. Throughout 2015, several activities took place prior to implementation including national advocacy, adaptation of CBA2I tools and materials to the Benin context, a training of a national cadre of trainers, and the training of the aides-soignantes on family planning and Noristerat-specific counseling, how to administer the injection, waste management, and record keeping. In addition, there were community sensitization and mobilization activities along with orientation workshops to ensure local communities, leaders, and health facility staff were familiar with the Advanced Strategy and to gain their buy-in and support.

The specific objectives of the evaluation reported in this brief were to:

- Assess the service delivery environment, including the safety and the quality of services provided by the aides-soignantes in the community and within health facilities.

- Measure client perceptions of the program including satisfaction with services received.

- Examine the perspectives and experiences of the aidessoignantes.

- Determine the number and characteristics of clients who received family planning methods, specifically Noristerat, from the aidessoignantes.

- Examine changes in numbers of new contraceptive users by method type at the health centers.

The Advanced Strategy began in August 2015. It was planned to last for six months but was extended to May 2016 because of a strike by the aides-soignantes during the pilot. During the strike, the trained aides-soignantes continue to provide family planning at the health centers and in the community on a limited basis. Monitoring and evaluation data was collected throughout the duration of the pilot to track the numbers of family planning acceptors, Noristerat acceptors, side effects, complications, and referrals for other methods. APC worked with a consultant to conduct an end-line assessment of key issues at the client, provider, and stakeholder levels to provide information to facilitate decision-making for scale up.

Study objectives

The goal of the assessment was to provide information to help the Benin MOH decide whether community-based provision of injectables should be brought to scale and if so, to provide guidance for scale up.

Study design and methods

This study was a mixed-method, post-test evaluation that included quantitative and qualitative methods. Structured interviews using a survey questionnaire were conducted with aides-soignantes and their family planning clients. In addition, data collectors directly observed provision of injectable contraceptives in health centers and recorded if the aidessoignantes performed the tasks on a checklist of required steps in injectable provision. Qualitative (in-depth) interviews using a semi-structured guide were also conducted with family planning clients to gain a deeper understanding of the acceptability of the Advanced Strategy. Finally, program records and service statistics were examined to determine the number of clients counseled by the aides-soignantes, the number who received a family planning method, and the number of new contraceptive users at the health centers involved in the inter vention. The study was approved by the National Health Research Ethics Committee of the Benin MOH.

Study setting

The evaluation took place in the communities and health centers of four boroughs in the Adja-Ouere commune where the aides-soignantes were trained: Adja-Ouere, Ikpinle, Ologo (Oko-Akare), and Tatonnoukon. Ten health centers and their surrounding villages were selected to participate.

Data collection

The study team was comprised of 10 registered midwives and nurses from outside the district and five local super visors. Data collection took place May 9–16, 2017. Sampling of the aides-soignantes was purposeful; the aim was to interview all 23 who were trained in CBA2I. All family planning clients who came to the health centers on the days the data collection team was there were asked to participate in the study. Those who agreed were interviewed by survey and their visit with the aidesoignante was observed. Observations were made in the health centers only to maintain client confidentiality. In-depth interviews were conducted with women who had received Noristerat from aides-soignantes as part of the Advanced Strategy. In-depth interview participants were randomly selected from the aides-soignantes’ registers and included clients who received services at the health center and in the community. They were called on the telephone or visited at home and asked to participate. Those who agreed were interviewed either in their home or at the health center, depending on their preference; no direct observations of service provision were made of women who participated in the in-depth interviews. Ultimately, the team interviewed 43 clients by survey and 94 by in-depth interview; 20 aidessoignantes by in-depth interview; and made 45 direct observations.

Results

The results are divided in four sections: quality of services; client experiences and satisfaction; experiences and perceptions of aides-soignantes; and examination of the program records and service statistics. The results presented include the survey interviews with clients and aides-soignantes, direct observations, in-depth interviews with clients, and program data.

Quality of services

The quality of injectable services provided by aides-soignantes was measured through direct observations of client visits. Observations focused on the welcome and initial consultation; counseling specific to Noristerat; and the injectable administration technique.

Observations of consultations between the aides-soignantes and clients show that generally they followed correct safety and good quality counseling procedures when administering injectables (see Table 1). During the welcome and initial consultation, between 95 and 100 percent welcomed the client, introduced themselves, asked the clients questions about the purpose of the visit, collected personal information, invited the client to ask questions, invited the client to make a decision herself regarding method selection, and used visual aids. Fewer (87 percent) aides-soignantes washed their hands before the consultation or explained the visit procedure to the client (71 percent).

With regard to specific counseling about Noristerat, 90 percent or more asked all the questions in the checklist, verified that the choice of injectables matched well with what the client wanted, and gave further information about the injectable including duration of effectiveness. Between 80 and 89 percent counseled about the mode of administration, advantages, common side effects and treatment, the appointment for reinjection, and made sure the client had a good understanding of the information provided.

In terms of the administration procedures, all the aides-soignantes were observed to inject Noristerat deep into the gluteal muscle, utilize the safety box to eliminate waste, and remind the client about her follow-up appointment. Further, over 90 percent had the appropriate equipment, gave the client a seat, informed the client about the care she would be given, complied with confidentiality while providing care, did not massage the injection site, rubbed the Noristerat solution between the palms of her hands, and stored the equipment properly after the appointment. Fewer (88 percent) were observed to wash their hands with soap and clean water prior to administering the injection.

Table 1. Percent of Aides-Soignantes Following Counseling and Noristerat Administration Procedures during Direct Observations

| WELCOME AND GENERAL COUNSELING | NORISTERAT COUNSELING | NORISTERAT ADMINISTRATION | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | % | Activity | % | Activity | % |

| Washed hands | 87 | Asked all questions in checklist | 90 | Had equipment | 91 |

| Welcomed client | 100 | Verified choice matched client’s wishes | 97 | Gave client a seat | 91 |

| Introduced herself | 96 | Gave information on duration | 92 | Informed about care | 91 |

| Explained visit/ procedure | 71 | Discussed mode of administration | 84 | Ensured confidentiality | 91 |

| Collected personal information | 98 | Discussed advantages | 87 | Washed hands | 88 |

| Asked about purpose of visit | 100 | Discussed side effects | 88 | Rubbed solution between palms | 90 |

| Used visual aids | 98 | Gave appointment for reinjection | 89 | Injected deep into gluteal muscles | 100 |

| Invited client to ask questions | 98 | Ensured client understood | 83 | Did not massage injection site | 90 |

| Invited client to make a selection | 98 | Used safety box | 100 | ||

| Packed the equipment | 95 | ||||

| Reminded client about next appointment | 100 | ||||

Client experiences and satisfaction

Of the clients who participated in the survey interview, 79 percent had no education; 84 percent were either married or in a common-law marriage; 76 percent were either Catholic or Protestant; 39 percent were housewives; 32 percent worked in commerce or sales; and 22 percent worked in agriculture. Over half (58 percent) were making a first-time visit to an aide-soignante for family planning; the rest were making a follow up visit. About three-fourths rated their reception as "good" and over 90 percent reported that the aide-soignantes invited them to ask questions, gave them the opportunity to choose which family planning method they wanted to use, and received additional information about the method they selected. About three-fourths said they understood everything the aide-soignante told them, although one-fourth said they understood most but not all of what they were told. Nearly all the women stated that they were confident about the method that they selected. Interestingly, nearly 90 percent felt that the length of the consultation was either "very long" or "a bit long." All said that they would return for their next appointment or consult the provider if they have problems. The problems that are most likely to prompt them to seek medical attention from a health center include severe headaches, absence of menstruation, and heavy bleeding; approximately two-thirds of the clients mentioned each of these side effects.

The majority (93 percent) of clients interviewed were very satisfied with the services they received from the aidessoignantes; 95 percent would recommend these services to a friend or family member. While satisfaction was high, clients suggested ways to improve family planning service delivery in general. About one-third felt that general awarenessraising was needed and another one-fifth thought it was necessary to educate men and husbands. Other suggestions (mentioned by fewer clients) included helping with side effects, increasing accessibility, and making services free. When asked specifically about their impressions of the Advanced Strategy, over one-fourth said they had a positive feeling about it. Sixteen percent reiterated the need to raise awareness among husbands, and a further 13 percent said that they like the community-based approach but do not want providers coming to their house and/or prefer going to the clinic.

These sentiments were supported by the in-depth interviews that were conducted with family planning clients selected from the registers of the aides-soignantes. The vast majority were very positive about the services provided by the aidessoignantes. They had confidence in the aides-soignantes and described them as competent, warm, and welcoming, and providing good-quality care. As one client said, "I have confidence in the family planning services she has brought to the village. She has educated us well and explained the different methods first and counseling and advantages."

While most clients were similarly supportive of the Advanced Strategy in theory, many did not want the aide-soignante coming to their house and some did not think injectables should be provided in the community. Many of these women stated that they preferred to get their services at the health center. About one-third of the in-depth interview respondents discussed the need for privacy and discretion, not wanting their husbands or neighbors to know they were using family planning because of general social norms against family planning use. Despite these concerns, most still supported the Advanced Strategy and acknowledged that there were other women in the community who would benefit from it, especially those who could not afford transport to the health center. These different opinions are described in the following quotes:

"It’s a good thing but society criticizes when we use family planning methods."

"Women don’t want to adopt family planning methods publicly, we want to do it in secret."

"Providing family planning at the community level is not a good thing because everyone will know what you are doing."

"It’s a good thing. I liked the service in the community. The community also likes it but there are certain men who do not want to hear about family planning in this village."

"The Advanced Strategy is very good because it helps us to reduce transport costs. But we want it to be discrete."

There was widespread consensus that there was a need for more sensitization of community members, especially husbands. Even those who did not want injectables provided at their home thought educating the public about family planning was useful. As one client noted, "They must continue doing sensitization so that everyone accepts and knows the benefits of family planning." Some mentioned how husbands believed that family planning use could lead to "prostitution" or "debauchery." There were many, however, who said their husbands were supportive of family planning use and some who were even encouraged by their husbands to start using it. As one noted, "It’s my husband who motivated me to do it." Others said that their religion is against family planning.

The majority wanted the Advanced Strategy to continue. In the words of one client, "I don’t want them to stop the strategy in the village. I want the products to always be available. Increase the education sessions, publicize with groups of women everywhere that family planning is a good thing." Many, however, expressed that they would like a wider range of methods to be available. As one client explained, "I support the community strategy but I am tired of injections, which is why I stopped in order to get Jadelle." Some wanted the aides-soignantes to come more frequently, especially to help with side effects. In addition, women mentioned cost and said that they wanted all methods to be free.

Aides-soignantes experiences and perceptions

The aides-soignantes largely expressed positive opinions about the program and their role in it. All of them believed this program is either important or very important (80 percent said very important) and nearly all are motivated or very motivated to participate in it. Nearly all (95 percent) reported that they felt they are more useful now and viewed their selection for the program as a promotion (84 percent).

In terms of workload, most (95 percent) said that they had enough time to provide family planning through the Advanced Strategy. On average, each aide-soignante worked in 4.3 villages and visited each village 3.2 times per month. The majority (90 percent) had a supervisor assigned to oversee their work on the pilot and reported that they received an average of 2.3 pilot-related supervisory visits in the past six months (with a range of 0–6 times). The majority (80 percent) had been formally introduced to the authorities in each village.

Based on their experiences, the aides-soignantes indicated several challenges and identified areas for improvement. The majority (60 percent) felt that at least some of the tasks were burdensome; 55 percent said that they found four or more activities burdensome. The following tasks were reported as burdensome by over half of the respondents: conducting initial counseling following the standard norms and guidelines; taking vital measurements; using the eligibility checklist to identify clients; providing Noristerat counseling according to standard guidelines; injecting Noristerat according to standard guidelines; handling injection waste; filling in the register correctly; explaining when to return for follow up: and explaining when it is necessar y to return immediately after Noristerat injection. Furthermore, nearly all the aidessoignantes said that they always felt uncomfortable using the job aid in front of the client during the consultation because they were concerned that it would make them appear incompetent.

In addition, they identified challenges that they faced daily. The following were reported by more than half of the respondents: lack of personnel; lack of transport; difficulty ensuring confidentiality in villages; lack of effective support from the relais communautaires (community health workers), unmotivated team; clients do not have money; difficult to track lost clients; transportation of equipment and tools; and informing clients about possible Noristerat side effects. The main suggestion they had to improve family planning services under the program was to provide the aides-soignantes with transportation.

Register review and service statistics

Over the period of the pilot program, the aides-soignantes provided family planning counseling to 660 clients. Of these, 463 adopted a family planning method; 449 adopted Noristerat. Those who wanted IUD, implants, or pills were referred to maternity facilities at the health center. There were no serious complications reported among the Noristerat users, although six women were referred for treatment of side effects. The relais communautaires working in the pilot area referred 181 women to the aides-soignantes for family planning.

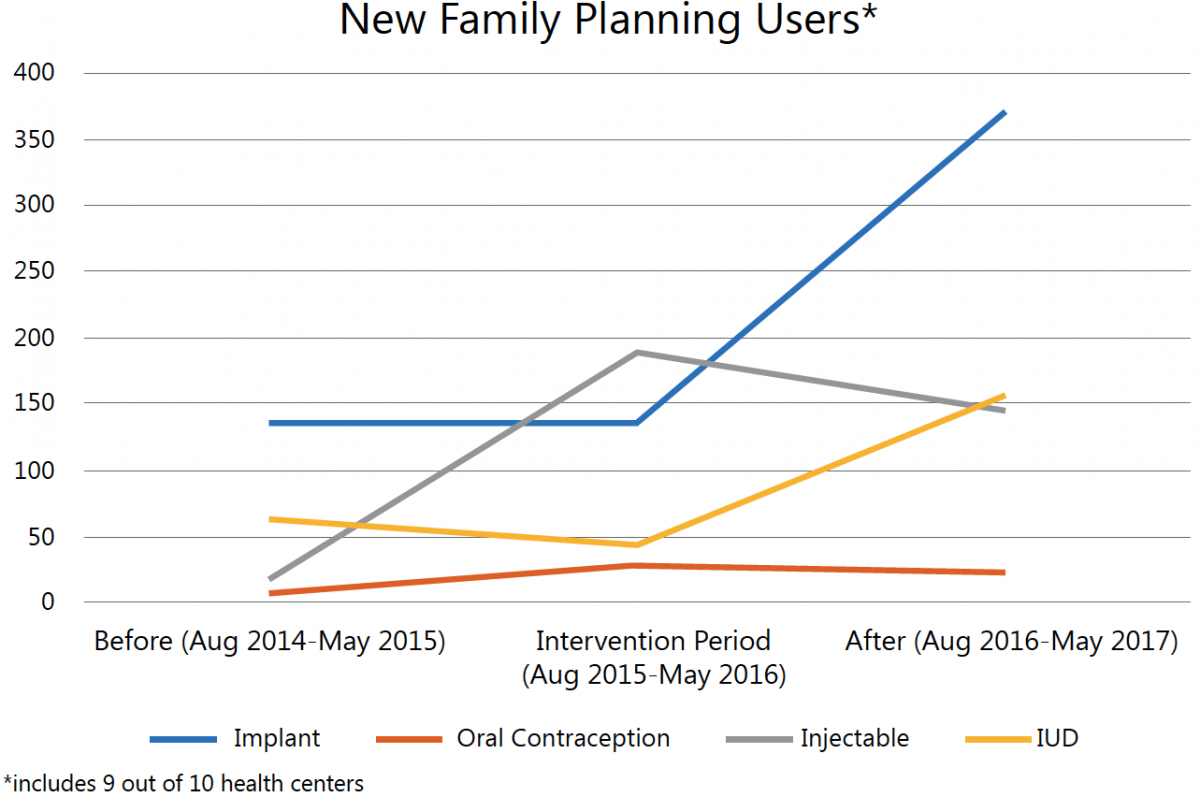

From health center service statistics, trends in method acceptance can be observed by examining the same months of the year before the intervention, the intervention period, and the year after the intervention (see Figure 1). The number of new users of injectables increased during the intervention period and while there were fewer new users the year after the intervention, the number of new acceptors is still higher than before the intervention. Further, the number of new oral contraceptive users (the only other short-term method available) remained relatively constant. The two longterm methods available, IUDs and implants, stayed relatively constant (with a slight decrease) until midway through the intervention period, after which there were large increases in the numbers of new users for both methods. This increase may be the result of a campaign run by a local NGO that promoted long-acting reversible contraceptives.

Figure 1. Number of new family planning users, August 2014-May 2017

Summary and recommendations

This evaluation demonstrated that aides-soignantes were providing safe and acceptable injectable services in the study areas and that clients were very satisfied with the ser vices they received. The direct observations showed that most aides-soignantes followed the steps for welcoming clients and providing Noristerat counseling and administration. An area for improvement is hand washing before providing the injection. While a high percent followed this procedure, supervisors should make sure that all aides-soignantes follow it without exception. It is important to note that the observations took place in the health centers only to protect the privacy and confidentiality of clients in the community. It will be important in the future for supervisors to observe the aides-soignantes in the community to verify the procedures in that setting.

Clients interviewed both by survey and through in-depth interviews were largely supportive of the services the aides-soignantes were providing through the Advanced Strategy and were very satisfied with the services they received. There were, however, concerns about community provision, with many women preferring the health center because it is more discreet. This issue should be explored further because it has implications for family planning provision in communities. It was widely thought that the aides-soignantes should provide more sensitization on family planning in general, especially with husbands, since there is still a lot of opposition to family planning in the communities, which leads many women to use contraceptives in secret. In addition, women asked for help in managing minor side effects and for a wider range of methods to be offered free.

Finally, the aides-soignantes were positive about the Advanced Strategy and welcomed their new responsibilities. They noted certain tasks that they found burdensome and challenges they faced. In particular, they were uncomfortable using the Noristerat job aid and eligibility checklist. Supervisors should gain a better understanding of these problems and help their aides-soignantes overcome them. Finally, health center service records showed an increase in new injectable users but no corresponding decreases in new acceptors of other methods, suggesting that users were new to contraception, not substituting for another method.

References

1 World Health Organization, U.S. Agency for International Development, (FHI) FHI. Community-Based Health Workers Can Safely and Effectively Administer Injectable Contraceptives: Conclusions from a Technical Consultation. Research Triangle Park (NC): FHI; 2009.